In Greek mythology, the Labyrinth was an elaborate, confusing structure built by the legendary artificer, Daedalus for King Minos of Crete to house the Minotaur. Legend has it that the Labyrinth was so complex that Daedalus himself barely escaped from it. Even Theseus, the slayer of the Minotaur, needed Ariadne’s thread to escape the Labyrinth, writes Abhi Chatterjee, chief investment strategist at Dynamic Planner.

To put it in perspective, the complexity of global financial markets has created a labyrinth, which is becoming increasingly difficult to navigate without its own Ariadne’s thread.

As investment professionals, we understand that effective navigation in the realm of investments begins with a clear understanding of our current position. By knowing where we stand, we can accurately assess our options and chart a course toward our desired destination. In this context, risk serves as the compass that guides us. It helps us evaluate the landscape of portfolio construction and instrument selection, enabling us to make informed decisions. However, risk itself is not a constant; it is a dynamic and ever-changing entity. Its manifestations vary across different asset classes, each with its own distinct characteristics.

To successfully construct portfolios, we need to delve into the foundational building blocks of risk. By comprehending the nuances of these elements and their individual dynamics, we gain the necessary insights to navigate the investment landscape effectively. This understanding empowers us to identify potential rewards and anticipate pitfalls over the investment horizon.

By acknowledging the dynamic nature of risk and deepening our knowledge of its components, we can equip ourselves with the tools to make informed investment decisions. This awareness enables us to adapt our strategies, construct portfolios that align with our clients’ objectives, and navigate the ever-evolving world of investments with confidence and foresight – in effect, providing us with Ariadne’s ball of thread.

To highlight the case in point, we will look at an example from the world of fixed income. Fixed Income instruments can be categorised by issuers as well as their credit rating, which is an independent assessment of the creditworthiness of the issuer.

To simplify, we have classified the issuers as government and corporate, and the credit rating as investment grade and high yield. In general, government bonds are the base relative to which the corporate bonds, both investment grade and high yield, are viewed, with the risk increasing as one goes from government bonds to investment grade to high yield.

Figure 1 shows the scatter plot of both the investment grade and high yield categories vis-à-vis those on the government bonds. In simple terms, the yield on the bonds represents the rate of return from these instruments if held to maturity from now.

Two facts are immediately apparent from the picture – firstly, yields on the riskier high yield bonds is higher than investment grade, signifying the extra compensation one receives for taking on more risk. Secondly, as the yield on the government bonds increase, so do the yields on the investment grade and high yield corporate bonds, but the rate of increase is not uniform, nor is it symmetric. The rate of increase in high yield is higher than the investment grade, given moves in the government yields. This is evidenced by the fact that while investment grade yields vary from 2% to 4%, high yield moves from 4% to 10%, as government bond yields increase.

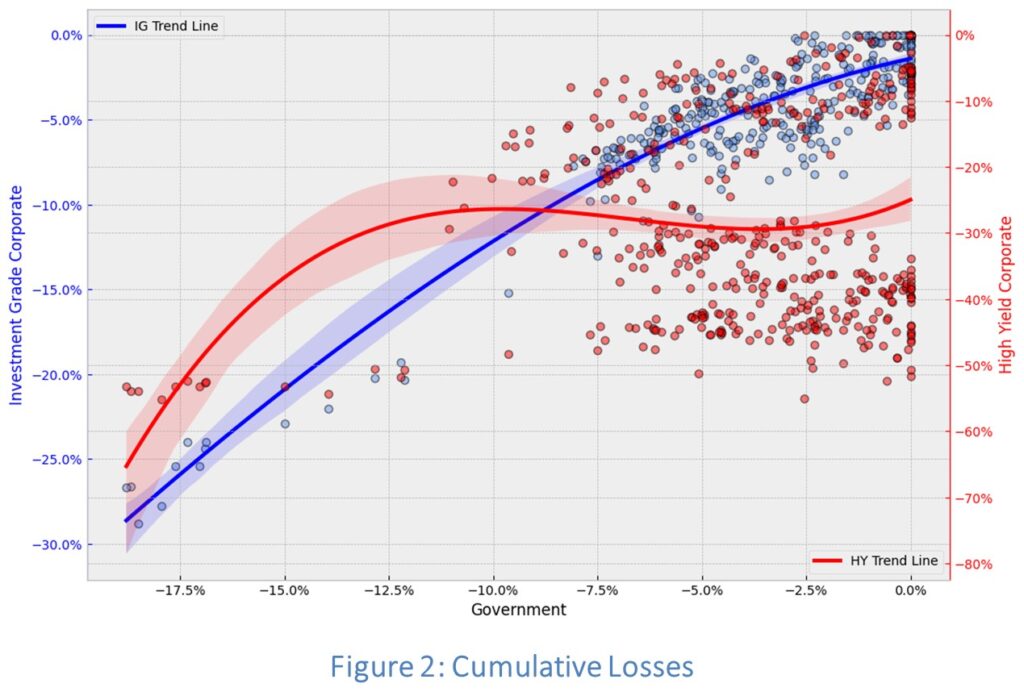

The impact of these moves can be seen from the chart on cumulative losses on the different fixed income asset classes. As the chart clearly shows, while losses in investment grade corporate bonds increase almost linearly with losses in government bonds, whereas in the case of high yield the losses exacerbate past a certain level.

In addition, in the range till -7.5% of losses in the UK government, the losses arising from high yield are unrelated, given the fact high yield as an asset class is positive correlated to equities rather than fixed income. But as the losses on government bonds increases, accelerating the uncertainty in the macro-economic conditions, high yield and equities face incremental and sizeable losses.

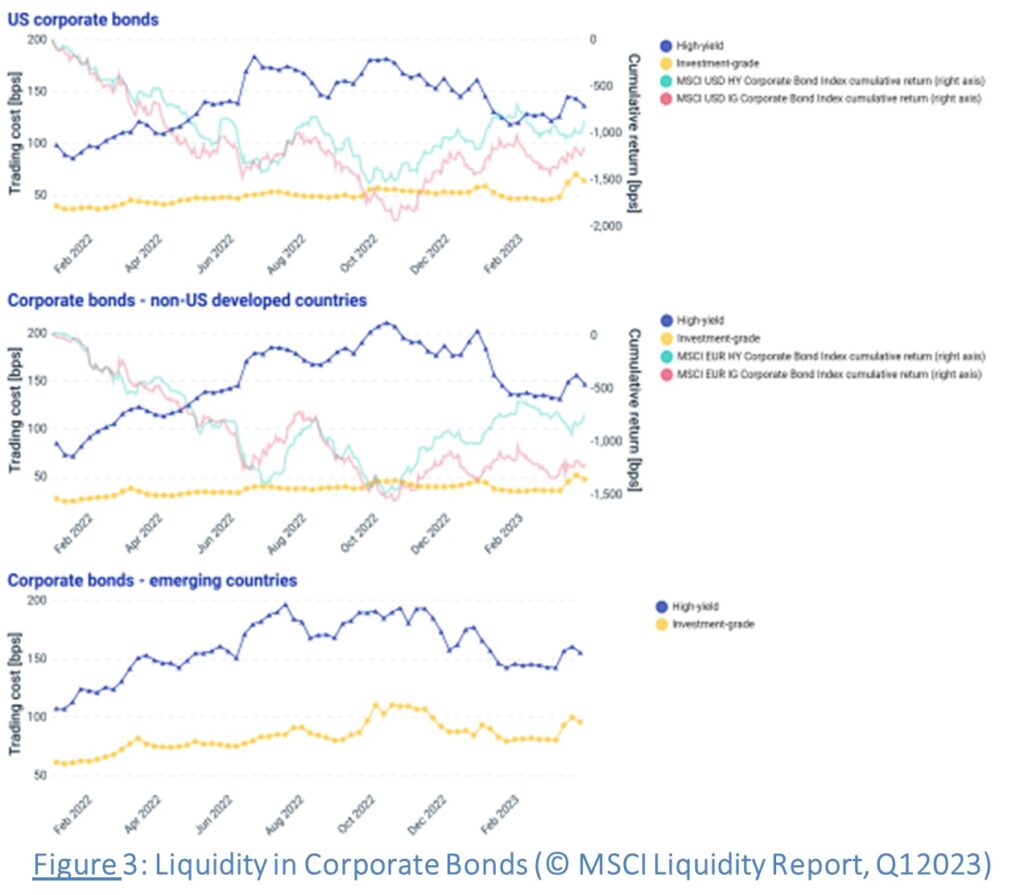

While market risk can be quantified with the help of models and assumptions, measuring and quantifying the liquidity risk in portfolios is challenging. In the simplest terms, liquidity risk refers to the risk of not being able to convert an asset to cash without incurring losses (technically known as haircuts). Market participants and portfolio managers often rely on qualitative assessments, expert judgment, and experience to manage and mitigate liquidity risk. They may also utilise various liquidity risk indicators and market-based measures such as bid-ask spreads, trading volumes, and transaction costs to gauge the liquidity of their portfolios.

Figure 3 shows the trading cost of investment grade and high yield bonds in terms of force selling these instruments. As can be seen from the graph, as prices drop, the trading cost on the high yield investments rise significantly, in comparison to investment grade, thereby rendering these holdings increasingly difficult to liquidate without a significant loss. This creates an added risk to solutions holding these kinds of instruments.

To conclude, knowing the holdings of a portfolio along with the characteristics of these holdings help us put risk in perspective. It demands a keen understanding and a calculated approach.

As we’ve explored the multifaceted nature of risk, from market risk to liquidity challenges, one thing becomes clear: while risk is a challenge to be reckoned with, a keep appreciation of its intricacies help us understand the investment landscape, and provide us with the thread to navigate the labyrinth, identify opportunities while mitigating its risks.

This article was written for International Adviser by Abhi Chatterjee, chief investment strategist at Dynamic Planner.