Whenever you build a portfolio for a client, two key criteria both need to be satisfied. First, the investment must offer good value. Second, it must fit with the identified future requirements the client is saving for.

Throughout the long years of quantitative easing (QE), many advisers concluded that gilts did not offer good value. The Bank of England (BoE) clearly wanted investors to sell their gilts back to it, not to be buyers of them, and the bank’s interventions were of a scale to move the market price. Today, however, the gilts market looks very different.

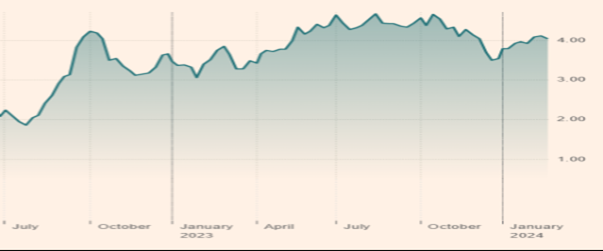

Fiscal uncertainties, accelerated by the Liz Truss/Kwarteng ‘Mini Budget’ announcement of 23 September 2022, led to UK 10-year gilt yields rising from 1.9% to 4.5% within just two months. They remained at roughly this level throughout 2023 – today standing close to that initial peak at just shy of 4%. Investors may wonder how long such a market opportunity will last.

10-year gilt yields rose dramatically after the infamous Mini Budget of 23 September 2022

Source: Financial Times Markets

According to Barclays analysts, during the past nine central bank interest rate hiking cycles, 10-year yields retreated roughly 18 months after the last central bank interest rate hike – though, of course, historic performance is never a guarantee of future performance. The last BoE interest rate increase, to 5.25%, was in August 2023 and that could well prove the high watermark as inflation appears to be stabilising ahead of falls expected through this summer.

Gilt trip

It is worth looking at where gilt yields have moved from. They naturally become relatively unattractive during periods of QE when the government of the day buys its own bonds to increase money supply – and the latest lengthy period of QE ran from 2009 to 2016 in response to the global financial crisis, when more than £455bn went into gilts. The BoE turned the taps back on in November 2020, buying billions of pounds of bonds in response to Covid 19 pressures. Most of that money – £875bn in all – was used to buy UK government bonds.

Today’s situation is all rather more stable than either the artificially stimulated QE years or the dash for growth that characterised Truss’s 44 days as prime minister. Whoever wins the coming general election will inherit this government’s recent tax cuts and even modest public spending will probably need fresh gilts issuance to finance it.

Indeed, only last month, the Treasury took the unusual step of opening up its latest new gilts issue to retail as well as institutional investors – and the supply and demand position suggests gilts are probably now at fair value. One clear advantage for those buying gilts, however is they are free of capital gains tax (CGT) free. This may be highly relevant for clients’ tax positions, as the CGT tax-free allowance has fallen from £12,300 last year to £6,000 this year and will fall again to just £3,000 in the next tax year.

‘Tax-free spot payment’

There are a wide range of maturity dates available and many gilts carry only a very small dividend, so you are almost buying a ‘tax-free spot payment’ at a specific future date. One option from a retirement planning perspective is to buy gilts that will mature at your projected retirement age. So, if you are 45, you could buy a very long-dated 20-year government bond.

Alternatively, if you want this holding to be inherited, you could decide to hold them much longer – perhaps for 50 years. Unlike savings held in bank and building society accounts, they will not be exposed to falling interest rates in the coming years – and, provided they are held to maturity, the yield they will deliver is fixed. Furthermore, if inflation is a concern for clients, then inflation-linked and fixed interest gilts can be purchased.

The investor who buys gilts will pay the market price on the day of purchase. We know the price will move to 100 or ‘par’ by its maturity date but the progression of that price can be anything but smooth. This may provide an opportunity to take profits along the way if the price rises above par. The price can also go down and, should the investor need money back before the maturity date, then those losses would have to be crystallised – hence the importance of checking the cashflows from gilts will meet investors projected needs.

Above all, gilts can be viewed as risk free. Whereas the issuers of corporate bonds can and do default, gilts – first issued back in 1694 – now have a 330-year unbroken track record of the British government never failing to make interest or principal payments as they fell due. As such, they can offer a useful counterbalance to higher-risk investments within a balanced portfolio.

Adrian Boulding is director of retirement strategy at Dunstan Thomas