We have heard much talk of the ‘magnificent seven’ stocks driving returns and market concentration in the US, as some of the largest technology companies have been a significant driver of the US stockmarket over recent years. Such companies have benefitted from growth tailwinds such as the proliferation of technology, monetary stimulus and in particular recent developments in artificial intelligence.

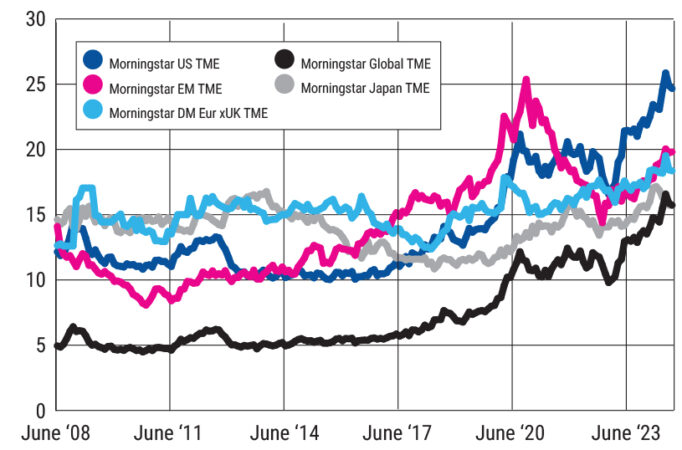

However, we have seen dominance from the largest stocks in markets globally, with many markets seeing a rise in concentration. Compared with the end of 2008, the share of the top five constituents in the Morningstar Global Target Market Exposure Index has tripled from 5% to 15.5%, as of the end of May 2024.

Morningstar Target Market Exposure Index (%)

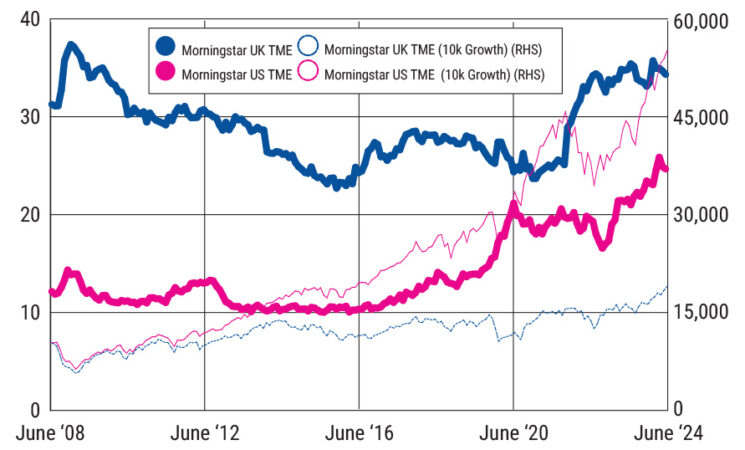

Although the US has been grabbing all of the headlines, the UK has historically been a more concentrated market. At its prior peak in 2008, the UK market was three times as concentrated as its US counterpart and remains so, despite the recent rise in US concentration.

See also: Near all professional investors expect to increase fixed income allocation over next 18 months

‘Value’ oriented sectors such as financials and energy, which constitute a large part of the UK market, have rallied since 2022, as a result of higher interest rates and sharply rising commodity prices. Meanwhile, as a value-leaning market, the UK has not benefitted from monetary stimulus and the proliferation of technology, which have proved growth tailwinds. In fact, concentration in the UK had been falling prior to 2022. The largest stocks continue to dominate market performance; for the five years to May 2024, the top 10 stocks contributed 60% of the total return, and while this was less than the 71% we saw in the US, this still meant that a limited number of stocks were driving the market.

But what does this mean for fund managers? Outperforming within such an environment is a significant challenge; and looking at UK large-cap equity funds, we found that managers were on average underweight to 11 of the 12 stocks which were in the top 10 index holdings from January 2022 to August 2024.

When we consider that only 25% of the stocks outside of these top 10 names were able to outperform the index by 10% or more over this period, it makes being overweight the largest stocks a necessary condition for outperformance. Meanwhile, many managers are reluctant to have such positions since they would pose a risk to diversification and since they often strive to differentiate themselves from their benchmark to generate excess returns.

Looking at the UK and US large-cap peer groups, we can see that the managers in the first quartile of performance, for both the UK and US, were more inclined to run up their concentration in the largest stocks in the period January 2022 to August 2024. In other words, continuing to hold ever increasing positions in the largest stocks was of clear benefit to investors. We saw a similar phenomenon during the prior run from 2006 to 2008, where funds in the top quartile had generally allowed concentration to rise as the largest stocks rallied.

See also: The asset allocator diary: Simon Evan-Cook

Critically though, after 2008, the tide turned and concentration started to fall, and through this period these funds which had been top-quartile performers in the run-up were at the bottom of the pack in both US and UK large-cap categories. Therefore, while running your top-cap winners might drive short-term performance, it can leave a portfolio overexposed and under-diversified.

However, concentration cycles can extend for some time, and given that timing the end of the cycle is next to impossible, it is not necessarily a bad thing to let concentration run up with the market. From an investors’ point of view, the best thing is likely to be continuing to hold a balanced portfolio, holding a good allocation to recent winners, to benefit from continued momentum, as well as those stocks which have been out of favour and will likely do well when the investment regime changes.

Should you swap your Nvidia stock for a basket of UK-listed miners? A bit of prudent rebalancing might go a long way, but keeping a balanced approach is likely to suit long-term returns.

Michael Born is an investment research analyst at Morningstar