The terms ‘Risk Capacity’ and ‘capacity for loss’ are often used interchangeably. This is a major problem, leading to unnecessary confusion, and unsuitable advice.

To clear up the confusion, we need to consider what it is we are actually trying to do when accounting for a ‘financial ability to take investment risk’.

The most important point to note is that the two terms aren’t at odds with each other. Capacity for loss is fully contained within the broader notion of Risk Capacity. If you measure Risk Capacity, you are – by definition and by default – measuring capacity for loss as a side effect. The reverse, however, is not true.

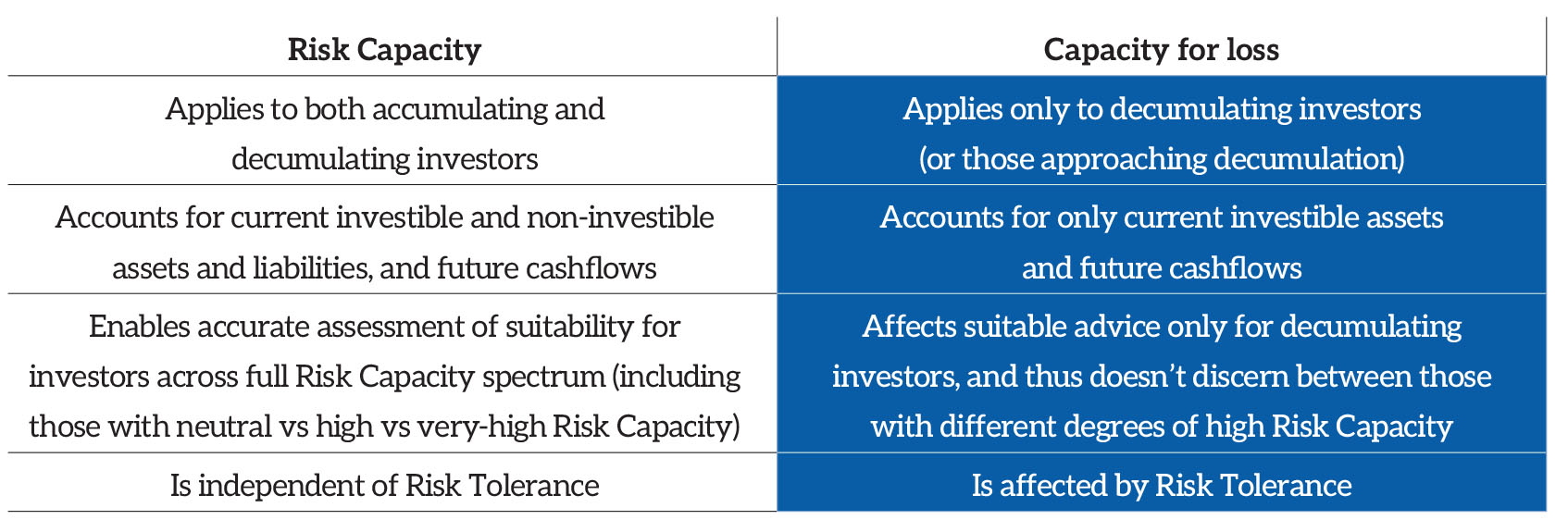

The differences have potentially vital consequences for the accuracy, consistency, and robustness of suitability assessments. In summary:

What do the regulations say?

Before expanding on each of these differences, it is important to note what the FCA has to say, not least because their recent Thematic Review into Retirement Income Advice has highlighted both the widespread nature of the confusion, and its unwelcome consequences.

The FCA’s May 2011 guidance defines ‘capacity for loss’ as: ‘the customer’s ability to absorb falls in the value of their investment,’ and notes that: ‘If any loss of capital would have a materially detrimental effect on their standard of living, this should be taken into account in assessing the risk that they are able to take.’

See also: The role of risk capacity in retirement income advice

Given their commitment to non-prescriptive rule-setting, the FCA must leave a fair amount open to interpretation. However, ‘open to interpretation’ too often leads to ‘tick off everything the regulations mention, as cursorily as possible’. This makes it necessary to look not only at what the regulations tell you to consider, but the role doing so plays in giving suitable advice.

It is through asking: ‘What role does ‘ability to take investment risk’ play in a suitability assessment?’ that the differences – and the importance of them – are made most clear.

1) Risk Capacity applies to both accumulating and decumulating investors; capacity for loss does not

The definition of ‘capacity for loss’ given above can apply only to investors near to, at, or post, retirement, because someone whose income fully covers their expenditure could arguably lose all their investible assets without any ‘materially detrimental effect on their standard of living’.

2) Risk Capacity accounts for all relevant financial circumstances; capacity for loss does not

If Risk Tolerance identifies your willingness to take risk in the long-term, Risk Capacity shows how this is influenced by where you are right now.

This clearly needs to include information about wider financial circumstances – both investible and non-investible assets, as well as current and future cashflows (including the extent of any associated insurance and emotional attachments to (usually non-investible) assets. The more you rely on your investible assets (relative to everything else you own, or will own) to fund your lifestyle, the less risk you are able to take with them.

3) Risk Capacity enables accurate assessment of suitability for all investors; capacity for loss does not

Because it accounts for non-investible assets, Risk Capacity differentiates suitable advice for investors based on their overall financial circumstances, while capacity for loss highlights only where current circumstances may be an issue or not.

Non-investible assets (such as a home) increase your ability to take risk with the money you can invest. This is because, relative to investors who don’t have these assets, they provide you with some buffer; you might not want to sell your home in an emergency, but you could do, whereas the person without such an asset could not.

Most investors’ main non-investible asset is their future earnings power. Young, educated, investors with a steady income, but few investments, have a very high capacity to take risk with their investible assets because their expenditure is funded from their income, and even if their investments tank, these are hardly relevant in the context of their lifetime earnings power.

All capacity for loss does in this situation is tell you that the young investor can afford to not worry too much about their current investible assets losing some short-term value. It doesn’t help calculate how much risk to take with them.

See also: Head to head: Pedal to the metal

When future spending and income are exactly in balance (accounting for size, timing, and priority of all cashflows in aggregate) then an investor’s current capacity for loss is near infinite… but they could be not far away from tipping into decumulation. This is quite different from an investor with 30 years’ worth of high savings potential ahead of them. Capacity for loss is blind to this difference, but it absolutely needs to be reflected in a capacity calculation, and subsequent suitability assessment.

4) Risk Capacity is independent of Risk Tolerance; capacity for loss is not

Capacity for loss tells us the extent to which a fall in investible assets affects your standard of living in the future. However, this is dependent upon your Risk Tolerance, because the less willing you are to take risk, the more a fall now means it’s harder to catch up later.

Risk Capacity, by contrast, tells us the right level of risk to take with investible assets, so as to align the risks of an investor’s overall wealth with their Risk Tolerance.

Your Risk Tolerance identifies how much risk you can take over your total wealth position. But your total wealth is different from your current investible assets. So, Risk Capacity essentially identifies how much to adjust for your current situation.

It provides a mathematical methodology for combining the importantly independent elements of an investor’s risk tolerance and their financial circumstances to assess the suitable risk level for that investor.

To be suitable, capacity calculations need to be comprehensive

Focusing on Risk Capacity rather than capacity for loss doesn’t downplay the importance of capacity for loss as defined by the FCA. Far from it. It ensures that it is fully incorporated within the appropriate wider context, relevant to those at every stage of their investment journey – seamlessly covering both accumulation and decumulation, and the vital transition between them.

Greg B Davies, PhD, is head of behavioural finance at Oxford Risk